Some usecases for GNU Units

Updated Sunday, Oct 12, 2025

As a studious GNU Units user, I have a small body of notes documenting various ways to perform calculations with unit conversions. Here are a few select ways that I found use of GNU units.

But first, a word about using GNU Units

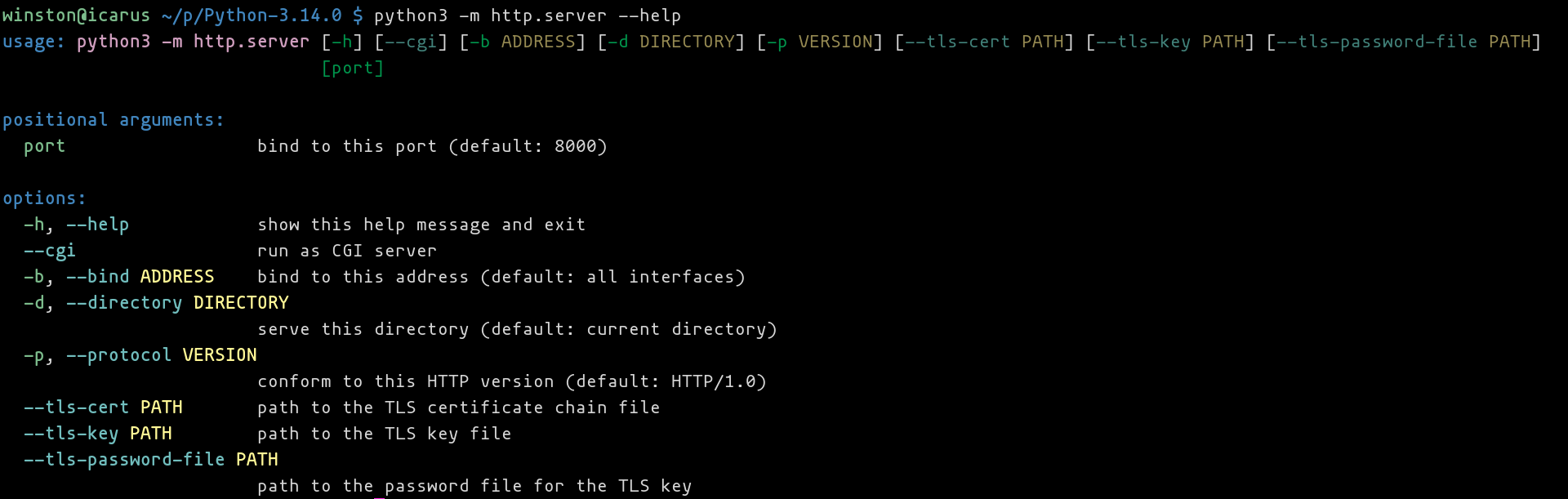

GNU Units is a powerful, free calculator that performs unit conversions for you. Please check out the examples on GNU Units’ homepage to see what it is capable of.

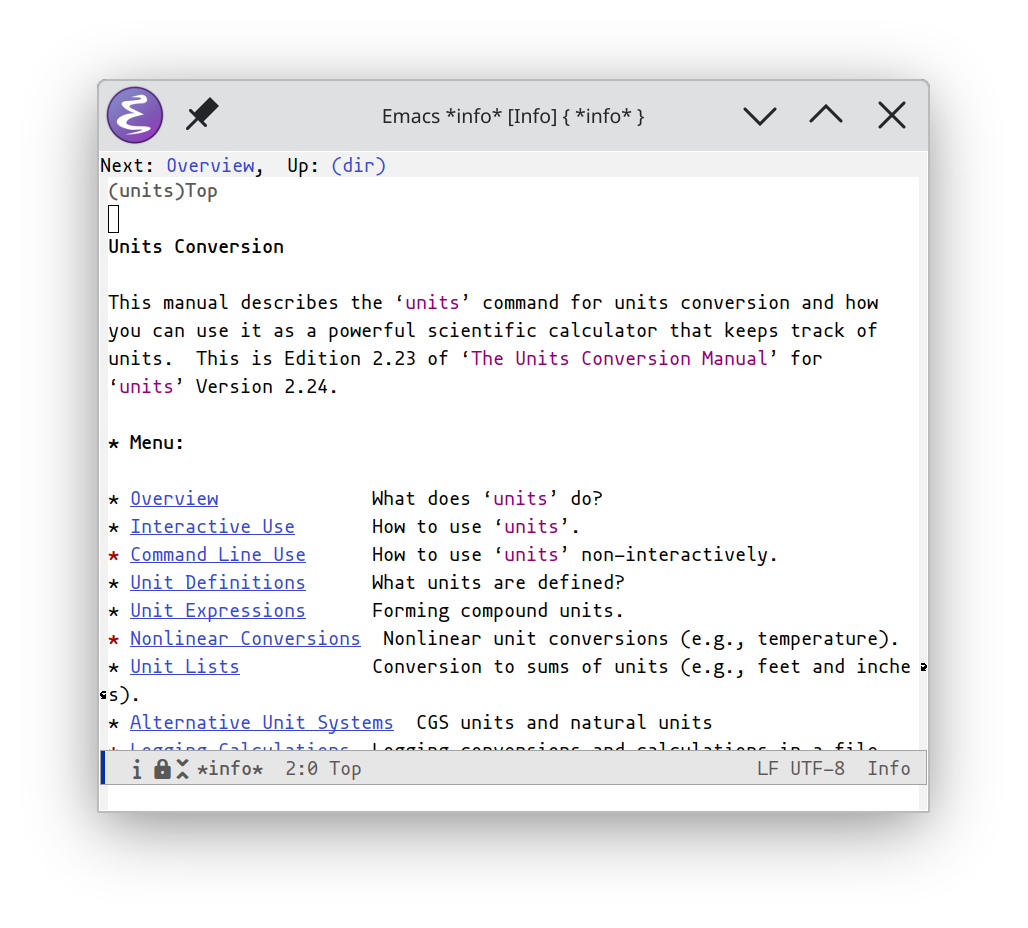

I encourage users to read the GNU Units documentation (link to the HTML

multi-page edition). Or read on the command line via info units or in Emacs

via M-x info RET m units RET (or running emacs like emacs -Q --eval '(info "units")'). As a self test, you ought to know what ;, |, _, degC(),

--verbose are for (hint, check the infopages index and this page!).

In order to understand its power, I recommend installing GNU Units on your phone (using something akin to Termux). Then use it whenever the need comes up to compute figures with unit conversions.

Calculate Aspartame intake via gum

Bought some especially hard gum to upkeep my jaw health called “Jawz Jaw Definining Gum Extra Tough Watermelon Gum”. Its ingredients are as follows:

sorbitol, gum base, xylitol, d-mannitol, moaltitol; less than 2% of: natural and artificial flavors, glycerin, citric acid, aspartame, acesulfame-k, bht to maintain freshness)

Each stick is 2.7g. Using GNU units, one can determine how much aspartame is contained in each stick:

units --quiet '2.7g 2%' mg

* 54

/ 0.018518519

From Wikipedia: According to EFSA acceptable daily intake (ADI) is 40mg/kg. FDA set ADI to 50mg/kg. Err on the side of caution. How many sticks a day can I consume before this intake approaches ADI?

units --quiet '161lb * 40mg/kg' 'mg'

* 2921.1349

/ 0.00034233271

Okay, that’s a lot of aspartame per day. Let’s calculate how many sticks:

units --quiet 'floor(161lb * 40mg/kg / 2.7g 2%)'

Definition: 54

So I can chew a ton of gum per day while maintaining ADI.

Determine grams per USD in protein powders

Comparing Dairy Free Vegan Protein Powder – Clean Simple Eats with Orgain Organic Vegan 21g Protein Powder - walmart.com

You have: (1.02 lb * (21g/46g)) / 19.59USD

You want: grams/USD

(1.02 lb * (21g/46g)) / 19.59USD = 10.781841 grams/USD

(1.02 lb * (21g/46g)) / 19.59USD = (1 / 0.092748535) grams/USD

You have: (990g * (18g/33g)) / 54.99USD

You want: grams/USD

(990g * (18g/33g)) / 54.99USD = 9.8199673 grams/USD

(990g * (18g/33g)) / 54.99USD = (1 / 0.10183333) grams/USD

Turns out Orgain is greater value but has peas so unsure about it.

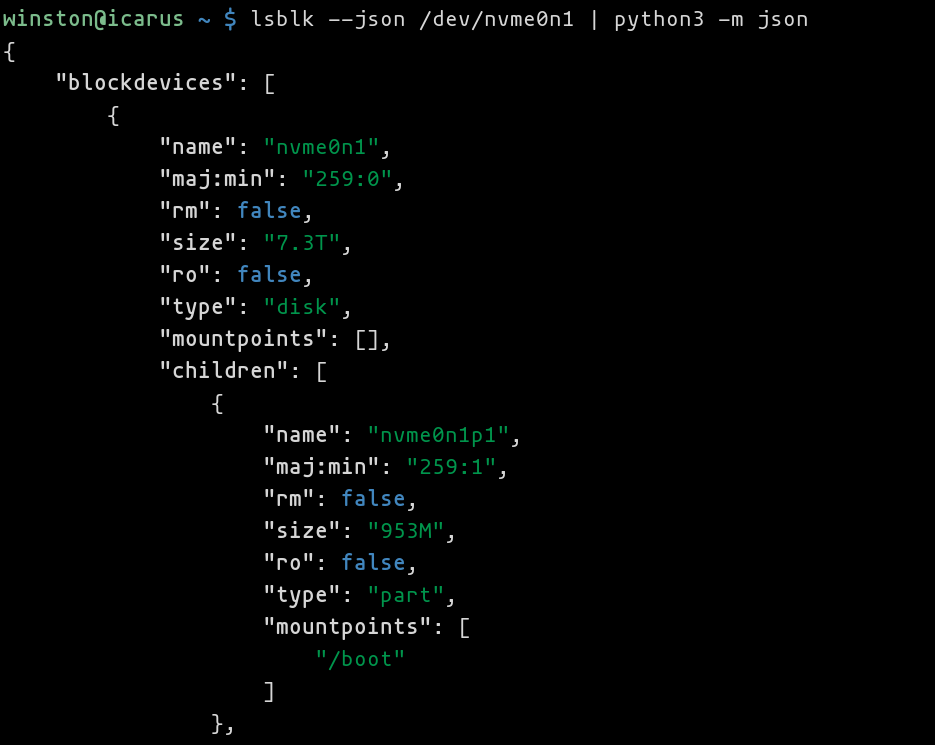

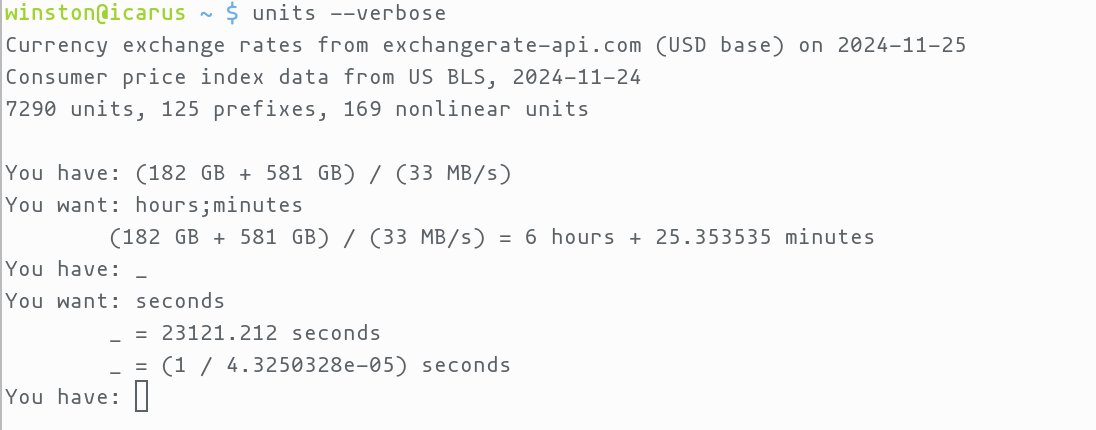

Determine datarate for zfs send

- check size in

zfs list - run

zfs sendand checkiostat -moutput for MB/s written to storage

You have: (182 GB + 581 GB) / (33 MB/s)

You want: hours;minutes

(182 GB + 581 GB) / (33 MB/s) = 6 hours + 25.353535 minutes

Currency exchange

winston@icarus ~ $ units

Currency exchange rates from exchangerate-api.com (USD base) on 2024-11-25

Consumer price index data from US BLS, 2024-11-24

7290 units, 125 prefixes, 169 nonlinear units

You have: 216.70 CZK

You want: USD

* 8.9405605

/ 0.11184981

You have:

Shipping weight

Weigh myself on scale with then without the package:

You have: 182.7 lb - 172.0 lb

You want: lb;oz

10 lb + 11.2 oz

That a wrap!

I have more examples tucked away in cobwebby folders stored on my less-used devices. And a lot more notes on unit conversions in general. Might be back with more unit nerd stuff…

In the meantime, check out some more examples in this Hacker News reply or this Reddit thread.