For the Lang Party Summer 2022, I wrote a BASIC interpreter. It took a bit of mental gymnastics and learning on my part. In this post I hope to share some of the experience in implementing this interpreter. For the curious, the code lives on GitHub.

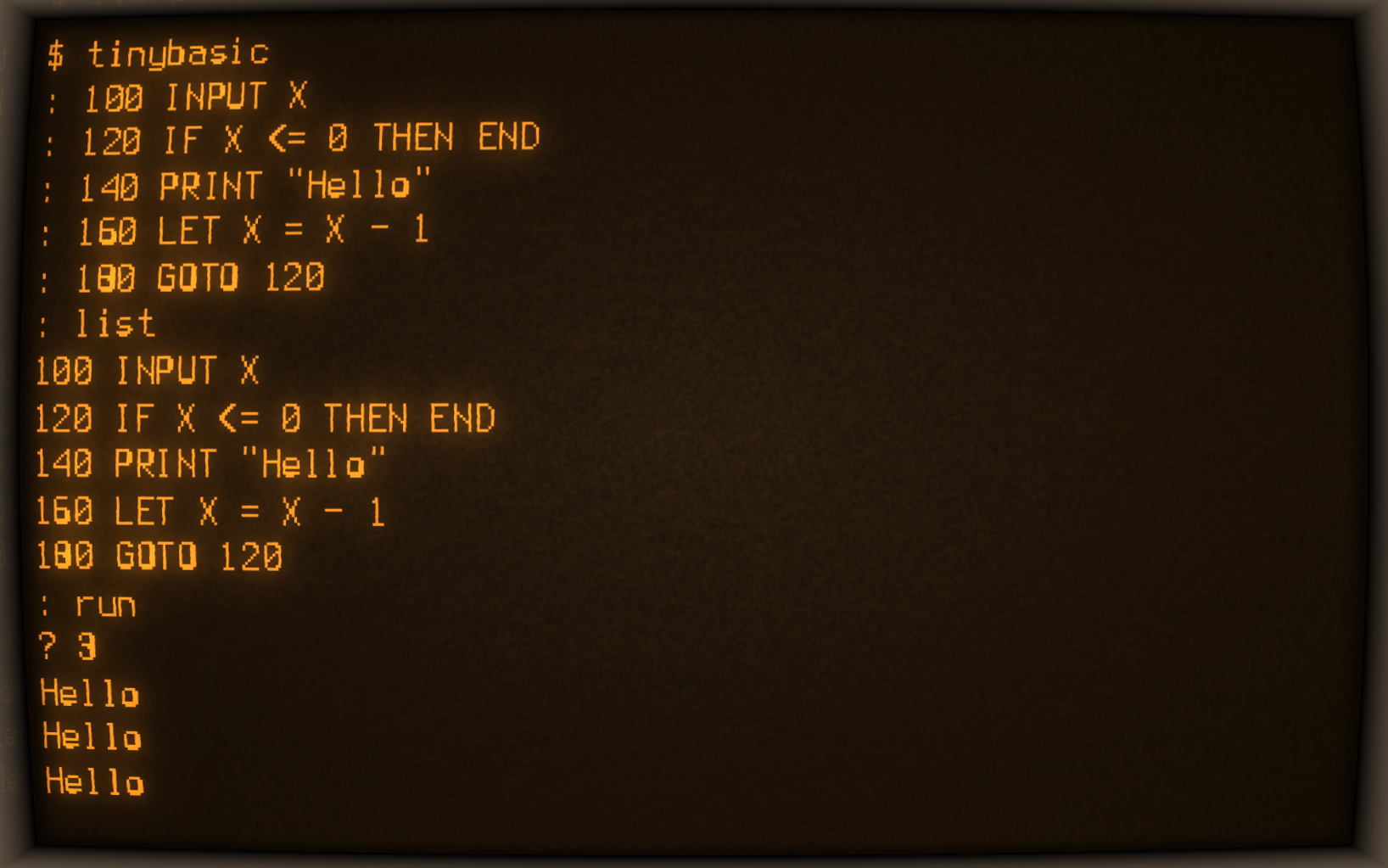

Figure 1: A TinyBASIC session in Cool Retro Term

§Try it out!

Want to try it out? Run raco pkg install --auto tinybasic to install it.

Then start the TinyBASIC monitor with either tinybasic or racket -l tinybasic. You should see a : prompt. Try PRINT "Hello".

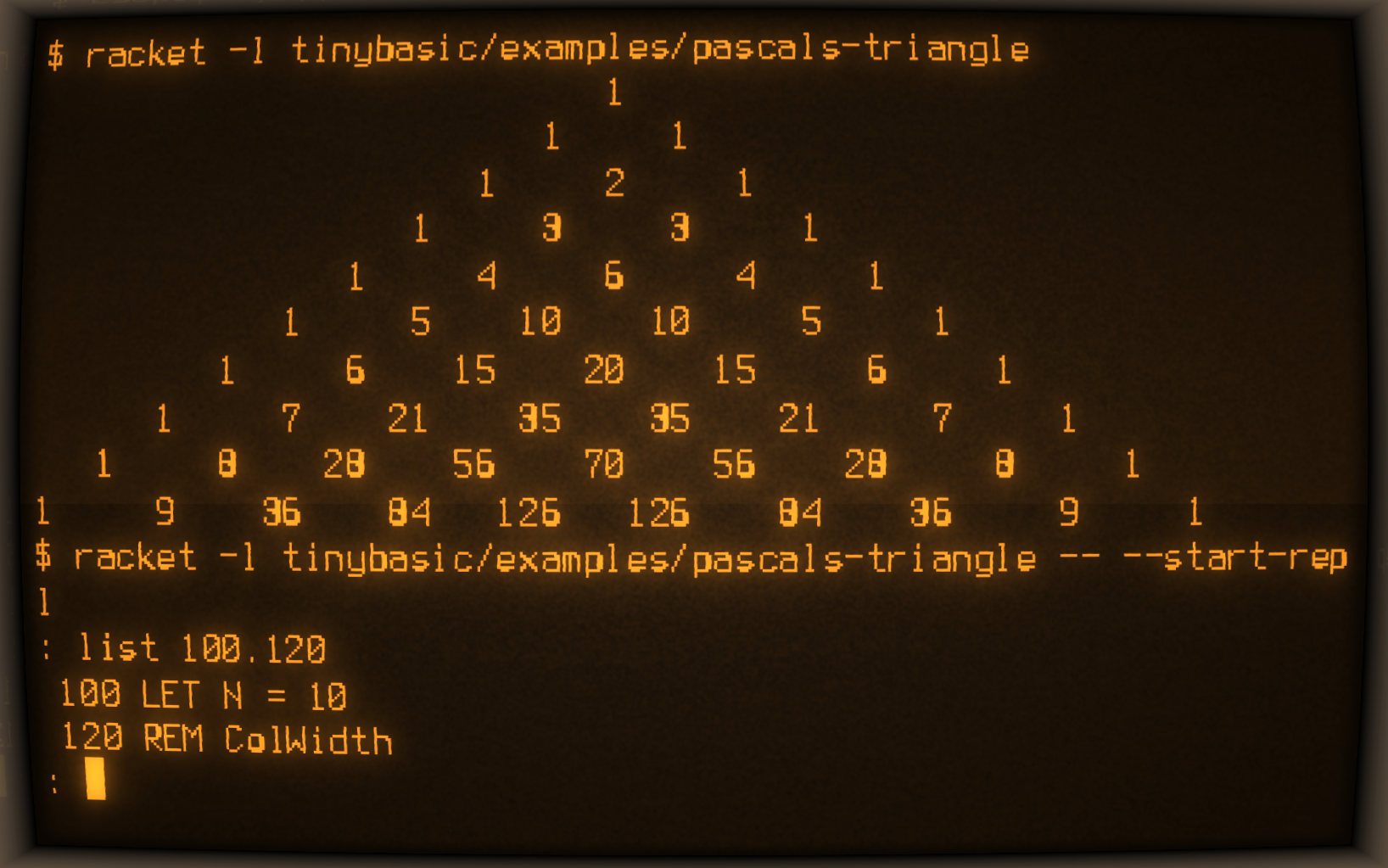

If you want to see a cooler example, here’s Pascal’s Triangle (source).

Run it with

either racket -l tinybasic/examples/pascals-triangle to execute the program,

then exit, or tack on -- --start-repl1 to load the program, then start the

Monitor/REPL.

Just so I don’t become a “How do I quit vim” meme: Use the BYE statement to

exit the monitor.

TinyBASIC does have a #lang. For example this source file works (call it

hello.rkt, then run via racket hello.rkt):

#lang tinybasic

100 print "Hello from tinybasic running in Racket!"

§Documentation?

The documentation is a bit sparse and iterative. You can read it here on docs.racket-lang.org. Be sure to review the git repository’s README here.

§Why BASIC? Isn’t it obsolete?

Yes! It is! One could also argue most tech is obsolete by the time we get it… there’s new concepts down the pipeline, iterations on old ideas, so on, and so forth. I think it’s valuable to understand where we came from, so that we (the technically inclined society) can avoid falling into hype traps in the future.

Years ago, I had the opportunity to visit The National Museum of Computing in

Bletchley Park, UK. There’s all sorts of cool stuff there, including a BBC

Computer with the BBC Basic Monitor open. It enticed me to interact - a simple

> prompt had me wondering: what the heck did people program on these things?

What was it like? Before I knew it I had the proverbial BASIC hello loop

running:

100 PRINT "Hello, world!"

120 GOTO 100

Figure 2: A BBC Microcomputer at The National Museum of Computing (2014)

It dawned on me, I’d like to implement a Basic Interpreter. The concept of

specifying line numbers and jumping to them with a GOTO statement felt

simplistic yet satisfying to see what could be done with it.

It turns out you could do the same stuff you can do today… however, there’s more cognitive burden on the language user: They must keep track of arbitrary line numbers in a Basic Program. The APIs seem far from rich, so that incurred a significant increase in development time (In my opinion). Program maintainability goes down the tubes. But we’re coding for fun here! Computing is fun! A wee bit of badness won’t hurt us!2

§Enter TinyBASIC

As I set out to build this interpreter, I was a little unsure defining a BASIC-like language on my own. Sure I could do it, but that wasn’t my goal - it was to implement some existing BASIC dialect. I’ve used enough programming languages to know it’s a bit of doing to define the language yourself and have it make sense in the way each statement interacts with each other. So I was surfing the web, pouring over Wikipedia articles to choose a BASIC dialect with the criteria of simplicity of design. The Wikipedia article on BASIC itself is a bit daunting, describing many sorts of keywords that seemed like sugar… an artifact of increasing programmer ergonomics in a fairly user-hostile language. I decided constructs like arrays, loops, and so on were out of scope. This excludes QuickBASIC, BBC BASIC, Liberty BASIC, not to mention object oriented BASICs like Gambas and VB.net.

I was also a little unsure how on earth you write a BASIC program. Is it parsed once when you enter the program into the monitor, or is it parsed every time? Does one parse an entire BASIC program? Or is it simply each line for itself? Then I discovered something amazing: there is a complete implementation of TinyBASIC published in Dr. Dobb’s Journal (read on Archive.org)!

I gave it a skim, it talked about things like pseudocode (maybe another phrase for bytecode?)… this felt a bit complicated too. I was a itching to start implementing. Regardless, it was clear - one could implement TinyBASIC in only a few whole pages of code (and it worked on old microcomputers!). I was sold. Referring to the Itty Bitty Computers “Tiny BASIC User Manual”, I began implementing a parser.

§Some implementation gotchas

Here I share some of the interesting weirdisms related to implementing TinyBasic. I wanted to practice using Racket’s Lex/Yacc clone to implement a parser, so I went with that tooling.

§TinyBASIC allows for garbage statements

At first, I tried defining the grammar in terms of an entire program. This was how we did it in compilers class. This is also how I see most languages implemented - you want to parse an entire program. Much to my chagrin, BASIC does not work this way. Tiny BASIC (and other BASICs of similar vintage) permit you to put garbage in your programs. For example this is a valid Tiny BASIC program:

100 GOTO 200

120 This is hot garbage in your program but tinybasic does not care!

140 Some more funny business on this line...

160 Okay let's get back to it...

200 PRINT "I ran successfully!"

220 END

When executed, line 100’s GOTO is executed, jumping over the invalid

statements. To support this program behavior, I considered permitting

the parser to parse bad statements as an invalid statement type in my abstract

syntax tree (the parsed representation of the code). This felt like a can of

worms. Then another gotcha hit me.

§LIST should show the program, verbatim

As I studied the TinyBASIC specification, there was another weirdism to consider. If I enter this program:

100 PRINT "Hello, world!"

120 END

Whitespace should be preserved when the program is LIST-ed back to the user.

This meant I had to keep a copy of each line’s verbatim text anyways. Based on

that requirement, I gave up on parsing all statements (even invalid ones).

Instead I implemented the line-reader code to read the line, determine if it

has a line number, then save the text for further parsing when executed.

This data structure looks like this: (struct line (lineno text entire). The

lineno contains either a line number (as a number) or #f (false) to

indicate there was no line number. text contains the statement to the right

of the line number, or the entire line. entire contains the entire line.

This is used to LIST the program verbatim.

When a line is evaluated, the interpreter parses the text field, then handles

parse errors accordingly. This is the unfortunate tradeoff of BASIC’s design -

you may not know if a valid program is composed of valid lines until it runs.

§Case insensitive tokens

I had a bit of a hurdle understanding how to implement a case insensitive Lexer

using the Racket Lexer. In the Racket Lexer language I could have written out

all possible alternations in case for every string. For example if I want to

make a case-insenitive if token, I’d have to write: (:union "if" "IF" "iF" "If"). Not quite the simplicity I was searching for! I asked on

StackOverflow and received an excellent answer. Here’s the macro I used to

implement a :ci operator for the Racket Lexer:

(define-lex-trans :ci

(λ (stx)

(syntax-case stx ()

[(_ s)

(let ([alternations

(datum->syntax

stx

(for/list ([c (in-string (syntax->datum #'s))])

`(:+ ,(char-upcase c) ,(char-downcase c))))])

#`(:: #,@alternations))])))

Now I can write (:ci "if") to match the above strings.

§Other minutiae

Much of this code was written with my ThinkPad x31. It’s a very comfortable

laptop, albeit a bit dated. To work around this, I discovered one could run

emacsclient -c -nw when SSH’d into another machine. This means I was able to

code as if I were on my desktop, but have this cozy ThinkPad coding experience

away from the desk.

While writing this post, I wanted to verify the code samples worked. To ensure

this (without copy-pasting), I wrote an Org Babel “plug-in” for running BASIC

snippets with tinybasic.rkt. It turned out to be a fairly simple task.

Duplicate a template file, search/replace some text, then add code like this to

the function that executes the BASIC code (See full listing in my emacs.d git

repository):

(org-babel-eval "racket -l tinybasic -- --run"

full-body)

Now I can position the cursor over the basic code listings, type C-c C-c,

then see the results of the execution below. Pretty neat huh? Confused?

Sorry! But here’s a YouTube video showing how this code evaluation feature can

be used.

§What’s next?

I hope to have documentation cleaned up shortly. That’s my main priority.

Then I hope to support DrRacket’s interactions window. Using #lang tinybasic

does not appear to start the tinybasic monitor properly in the interactions

window. Finally, there may be some crazy ideas to try out, such as adding a

RACKET statement to evaluate arbitrary racket code. That would be cool!

Oh and testing would be fabulous… this project was a test in what can be done. So I embarrassingly skipped writing a single unit test, contrary to my usual personality of demanding tests on everything. Oh well, it was fun. What can I say? I hope nobody is using this in production! 😉

Thanks for reading. If you have any comments about the code, please feel free to reach out to me directly or open an issue on GitHub.

-

The

--terminatesracket’s own argument parser, and passes the--start-replargument to the loaded module’s command line parser. 🤷 It works! ↩︎ -

Structured programming, while out of scope in my interpreter, helps maintainability significantly. The difference between writing a loop using

GOTOand aFORloop is night and day. ↩︎